Aging, logic and bioethics

It’s been said before, but worth repeating: the bioethical priorities and concerns of developed and developing nations are sometimes poles apart, revealing striking differences in mentality, values and power. A case in point is a recent article in The Journal of Medical Ethics, entitled “Life extension, human rights, and the rational refinement of repugnance”. In it, the author -- a self-described biogerontologist – claims that aging is “humanity’s foremost remaining scourge”, that we are “within striking distance” of curing aging, and that those of us who are wary of the idea of radical life-extension via biotechnology are simply backward. All of this may sound strange to those living in countries with scourges more pressing than aging, or rather, where many people die of preventable diseases before getting much of a chance to age.

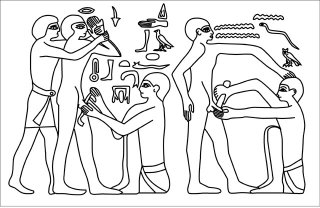

Then again, the notion of ‘curing aging’ probably sounds strange no matter where you are. Aging to most people is as natural as being born; it is what people do, or what at least their bodies do, between being born and being dead. Most people don’t like it much, but it is accepted as part of the picture of what life is like, and what we have in common with other creatures as well as what we share with environmental cycles of growth, decay, death and regeneration. This is probably why it is unsettling to hear aging turned from a feature of the human condition into an affliction – like gonorrhea – that we might get rid of with injections and pills.

The author of the piece (A.D.N.J. de Gray) contends that we should all embrace radical life extension in so far as we embrace logic and human rights. We all – except perhaps death penalty advocates – embrace the right of a healthy human being to go on living, and it is simply a matter of logical consistency to then embrace the related right to cure aging through the use of biotechnology. Our moral intuitions about aging as a human condition will be overcome by rational argument, or at least that is the way things work in Cambridge (England) where de Gray is located.

According to the author, bioethicists have a special role to play in this debate. Being especially logical folks, and being independent of the politics that pervades science (at least in Cambridge), bioethicists are in a position to persuade the masses to give up their irrational attachment to aging. They can demonstrate through rational argument that, despite vulgar appearances, ‘going on living’ indefinitely by means of sophisticated drugs actually accords with our deepest moral values. In other words, bioethics can do humanity a service by doing PR work for the anti-aging enhancement industry.

But who knows, maybe bioethicists can play another, less slavish role. They could namely critically reflect on what living 150 years might mean for ordinary persons -- its impacts on core spheres of existence such as interpersonal relationships, family life, and work – and offer a nuanced opinion that neither glorifies nor condemns the possibility of extending lifespans. All this, while affirming something that every poor Malawian villager knows: that death, even in Cambridge, waits for us all.